|

Notes

on a Difficult Film Notes

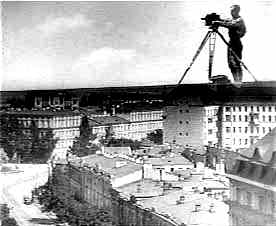

on a Difficult FilmAs filmmaker Dziga Vertov (his real Polish birth-name was Dennis Kaufmann) warns: 'VIEWER BEWARE!' If you are looking for a narrative film, this is not it. There is no plot, no story, no characters. This is a documentary view of a Moscow day, from sleep, to wake, to work, to play. The closest to a character is the ever-intrusive filmmaker as he trots about making the film. (But who is filming the filmmaker making the film?) The filmmaker calls it an experiment in creating a "truly international language of film... free of narrative". In the 1920s and before, there was little distinction between experimental and commercial film. The film was released in the United States as "Living Russia" and was shown as regular fare along with Chaplin's and Clara Bow's latest. Kaufmann's word 'experiment' is important. As with any well-conducted experiment, the result is not important but the rigorous conduct of the experiment is. Whether Kaufmann 'succeeds' in creating a "truly international language of film... free of narrative", free of cultural bias, as in science, is for you to decide. Yes or No are both valid choices. Using the word 'experiment', Kaufmann attempts to ally the film with the authority of Science. As Kaufman says, the film is about the 'visible'. It is not about things hidden or emotions or narrative threads but only about what can be seen now, what is scientifically verifiable. Part of the difficulty with the film is this Scientific Materialism, to which most Soviet artists subscribed, including the great Russian filmmaker Eisenstein. After 100 years of viewing films and 50 years of television, we expect the screen to contain a story, we expect an object, a face, an action to 'mean' something beyond itself. But this film is only interested in surfaces, and in the similarity of surfaces and the movement of surfaces in space. In spite of that, what does emerge is an almost charming, innocent and unique view of urban Russian culture as vibrant and alive. At least in the belle epoch of 1928, the year the film was shot. In 1928, Stalin was consolidating his power and started the first Five-Year Plan of forced industrialization and disastrous collective farming. The film shows homeless people (a result of forced industrialization?) sleeping on park benches. But by the 1930s, Stalin, the tireless Russian film Czar, grew to dislike the film and banned it. There had also been a shift away from international scientific materialism towards Russian nationalism. Eisenstien was a victim of this shift who redeemed himself in the eyes of Stalin with his stirring Russian narrative tale, 'Alexander Nevsky'. The experiment for Russian filmmakers was over. What is one to do with a film whose time has come and gone? The camera tricks now seem stale. The split images and forced perspectives are no longer fresh. We have assimilated the visual aspects of the film. Can we recapture what it was like for the first viewers of this film? When seeing a moving image in the screen was magic enough? A poignancy arises when we contrast these happy and energetic people with the fate to come under Stalin's excesses and World War Two, in the broad narrative of Russian history. |